Ton de Leeuw and Cornelius Cardew :

Mountains at Boswil 1977

by Chris Cundy

There are two works called ‘Mountains’ both written in 1977 and both dedicated to the renowned Dutch bass clarinettist Harry Sparnaay. A year earlier Sparnaay was visiting Boswil in Switzerland for an international conference on the theme of ‘Der Komponist als Mitarbeiter’ (The Composer as Collaborator) and here he struck up a friendship with the English composer Cornelius Cardew. He invited Cardew to write a new work and their tantalizing surroundings near the foot of the Lindberg mountain presumably suggested the choice of title. The other work to be commissioned by Sparnaay that year was by the Dutch composer Ton de Leeuw. Is it possible that de Leeuw was also attending the Boswil conference, and if so, was there something else they shared that might result in the works having the same title? I’ve known about both pieces for some time but I’ve often wondered if there’s any lasting connection between the two Mountains? First impressions reveal a gulf of differences - the Cardew is a set of variations on a theme taken from JS Bach. Whereas the de Leeuw plays out uninterruptedly on long phrases derived from North Indian traditional Dhrupad vocal music.[1] Occupying such opposite realms, is there any point in looking for seeds of a deeper kinship between the two? This is confounded further by the fact that only one of the pieces was actually performed by Sparnaay.

With regards to the Cardew it should be noted that a draft copy was originally returned by Sparnaay suggesting a few changes - which is common practice. This had been happily agreed but a revised version never materialised and Cardew died very suddenly in a hit and run incident four years later when he was only 45. A work titled ‘Mountains’ by Cardew was published posthumously as a facsimile from a handwritten manuscript and appears to be complete albeit with a few hesitant corrections and a crossed-out double repeat bar.[2] It’s not the only late work by Cardew that didn’t reach a publishing house and his priorities at this time were more active elsewhere in radical left-wing politics. The Ton de Leeuw is also a handwritten facsimile but it has a publisher’s date of 1977.[3] This piece also sets itself apart from Cardew’s in that it is accompanied by a pre-recorded electronic counterpart, originally reproduced on a stereo tape machine with time-codings for the player to follow in the score. It's worth noting that Harry Sparnaay did make slight alterations to the de Leeuw score, and the original recording he made for the Donemus 'Composers' Voice' label reveals a repositioning in the extreme altissimo registers towards the latter passages of the work.

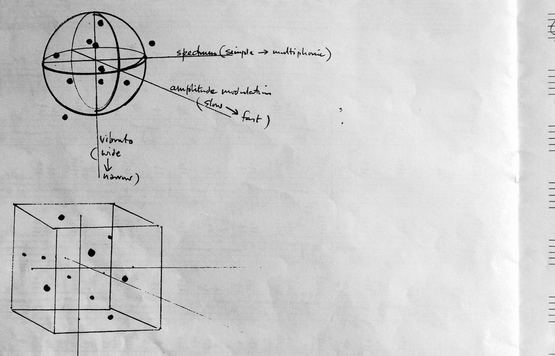

I. Graphic elements, second variation: Cardew

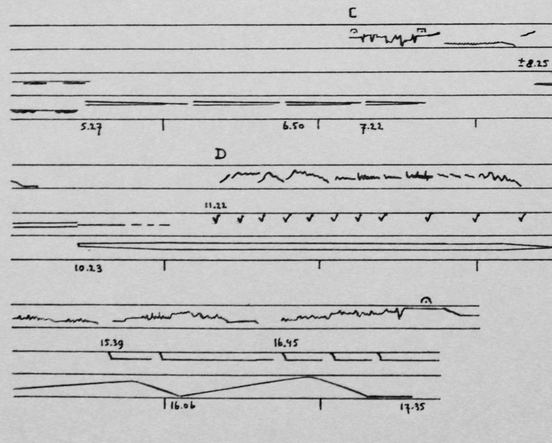

II. Graphic elements: de Leeuw

Although these works are conventional and use standard notation - each following a linear sequence, there are also graphic elements to be found in both. This is where things start to get interesting because by now Cardew had turned his back flatly on the avant-garde world that he was so much a part of in the 1950’s and 60’s - and expressed most fully in his groundbreaking graphic score Treatise (1963-67). Around the same time he was writing Mountains he had published a critique re-evaluating and questioning the validity of graphic scoring - Wiggly Lines and Wobbly Music appeared in Studio International in 1976. In the article he stakes out his position: “In 1972 I was asked to speak at a conference on problems of notation in Rome, and spoke of my own composition Treatise as a particularly striking outbreak of what I diagnosed as a disease of notation, namely the tendency for musical notations to become aesthetic objects [...]”.[4] For Cardew Mountains cannot be a transitional piece but neither should it be seen as a complete anomaly. The graphic section in it is both sonically and visually unexpected but it does tie in with the works initial theme. The player is given a set of pitches in a descending order and invited to explore each as if it were a ‘New Vista’ in terms of volume, amplitude modulation, multiphonics, or free playing and this forms a whole variation of its own on the fourth page of the score. In de Leeuws piece the graphic element also serves a functional role, but it works more as a companion or abstract to the notated score, as if the entire duration of the piece can be seen as a vast and enveloping landscape.

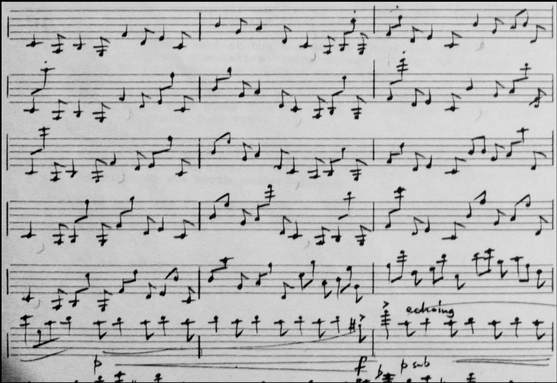

Closer scrutiny of the Ton de Leeuw reveals that the work is divided into five different sequences. Momentarily the piece begins with the bass clarinet alone, playing a single bar of 9/4. This is a quick gesture that rises and falls on a slowing arc, then the tape begins with everything settling into a square modal progression. Repeated lines roll out over the continual whirring sounds omitting from plus and minus voltage control resistors on the tape.[5] The following sequence falls into gradual and descending trills, flutters, and then a subtle reminder of the gesture that’s heard at the outset. It’s a neat drawing out of a short and intense phrase that extends into a simple clear sound. The Cardew also begins with a short phrase before rolling out into repeated modal progressions. In his piece the progression expands concertina-like towards extreme registers of the instrument using a two part counterpoint based on the theme. This first variation of the Cardew is marked ‘Bowling Along’ and the theme - lifted note for note from the Gigue of JS Bach’s solo keyboard Partita No.6 in E-minor, forms a mirror image on the page with the first line reflected upside down in the outline of the second. It’s a butterfly effect that informs a widening of simple, repeated tonalities throughout the rest of the piece. Unlike so-called Minimalist music the effect is at times knotty and occasionally clumsy on the fingers with a respite half-way for calling echos either loud to quiet, or the other way around. It’s after this that we are thrown into the long descending vistas that form the graphic section.

III. Detail of first variation: Cardew

At this point in their careers both composers had gone against the exuberant trends and expansions of atonal music that had dominated contemporary music from the 1950’s onwards, practices that had been venerated by Karlheinz Stockhausen and derived from Anton Webern. Having studied ethnomusicology in the early 50’s Ton de Leeuw found it difficult to join ranks with this school of thought and had accused Stockhausen of adopting an appallingly superficial assessment of oriental music.[6] In his article Back to the Source (1996) de Leeuw explains that his first encounter with Stockhausen “[...] made me deeply uneasy and to this day I wonder at my continued admiration for Webern in the face of this ideological smoke screen”.[7] Cornelius Cardew had worked closely with Stockhausen two decades earlier, and had collaborated on final drafts for Carré (1959-1960) - a work for four choirs and four orchestras. For him Stockhausen had become an object of the bourgeois impasse. Stockhausen Serves Imperialism was published in 1974 [8] - it’s a polemical text which acts as a personal statement for Cardew’s own political awakening governed at that time by the writings of Mao Tse Tung.[9] With hindsight there must be glaring inconsistencies when it comes to squaring the class struggle - through the prism of Western music, with the unspeakable horrors we now know about Mao Tse Tung’s regime. But unlike most ‘political’ composers Cardew was more than just an idealist narrator, he was an activist. He even served time for it and was sentenced to six weeks at HMP Pentonville in 1980 for acting against Racist events and obstructing National Front campaigns in London and Birmingham.[10]

Ton de Leeuw’s writings have a more subtle political expression, but like Cardew he is concerned with the problems of economic conditioning, the absence of what he sees as an ethical, artistic, or spiritual foundation in our time, and that “[...] this has resulted in a deceptive world, a superficial culture that appears difficult to mend".[11] There is a concern in his music to learn something from a spiritual past, not to make approximations but to extend something from it, and by doing so - to validate a contemporary practice. In Mountains de Leeuw has referred to his use of Dhrupad, ancient Hindustani song form which can be found in the compositions circular progression of modes, its continuous accompaniment, and in the long diatonic phraseology which is characteristic throughout the whole piece. But the choice of instrumentation of bass clarinet and electronics distances the listener from direct comparisons. Dhrupad being a Sanskrit word, deriving from the singular dhruva - meaning immovable or permanent, and pad - verse.

IV. Detail of first sequence: de Leeuw

Cardew’s spiritual homecoming was a more complex journey. The year in which he died he had enrolled at King’s College London to study a Masters in Music Analysis. It’s curious to see that some of his later works begin to reference aspects of a pre-romantic era music, and it appears that Mountains stumbles upon a moment when he was addressing these issues very openly. The third variation of the score is marked ‘Cadenza’ and is fully notated, only without bar lines suggesting the speed and agility of a baroque improvisation again referencing the music of JS Bach. The Cadenza is a single page of rising and falling arpeggios - a visual play on the outline of a mountain range. Comparing this with de Leeuw’s score, there is no Cadenza - and there is no obvious partitioning between the five phases of the piece, but there are many aspects in the writing that play visual games. Subtle inversions and mirror images, the rapid ups and downs of the tongued decrescendos and crescendos for example, and the sudden arpeggios starting out at the fourth sequence. Whether ascending or descending, each arpeggio run gets tucked between the staves or falls on the stave lines depending on the order of their opposite succession. Again, the emphasis is that a visual and musical duality pervades each of these works. The final variation of Cardew’s score is marked ‘Exuberant’. It’s more disjointed than the previous material and begins with a set of fanfare-type phrases before changing course into a leaping frenetic passage. The closing moments of the piece offer a brief decrescendo marked ‘New Growth’ and a symmetrical ‘Fantasy’ in 12/8 time before reaching a blunt finale where the very last phrases have optional, and undecided suggestions for slap tongue or cross fingering.

These works were cast from a friendship at Boswil. But the two ‘Mountains’ remain quite different from each other with Cardew’s showing a restlessness, whereas de Leeuw’s possesses a calmer, perhaps more cohesive centre at its compass. Both are concerned with tracing distant sources and seeking their relevance in contemporary practice. Of course this isn’t unique and even in Cardew’s pre-political work we find some traces of English medieval choral music - this is evident in Unintended Piano Music (1969), or The Great Learning Paragraph 3 (1970) for example, both reminders that in his youth he had begun his musical life as head choir boy at Canterbury Cathedral. De Leeuw’s career and musical journey is almost entirely concerned with re-sourcing living traditions from his travels, most significantly to India, Japan, and also Scotland - the use of Gaelic Psalms sourced from the Hebrides can be found in his choral work Car Nos Vignes Sont en Fleur (1981) for example.[12] For Ton de Leeuw it was a pursuit in reaching a spiritual meaning, finding a context, and in resolving the technocracies that were plaguing the music establishment. For Cardew this was an avenue in which he could address a personal conflict of interest - between his political activities which took priority, and which would ultimately consume him, and in reinventing himself as a composer who, for those very reasons, had rejected the avant garde. Both had questioned the wider social implications of music, but to end with de Leeuw’s words - “[...] The quality of music is not determined by theories. In our century, many artists have, to varying degrees, been led astray by stuffing their work full of theory, psychology, politics, and what have you. It should be clear that the creative fantasy never frees itself if we remain immersed in speculations”.[13]

© Chris Cundy | October 2017

Thanks to Horace Cardew, Davo van Person, and Harry Sparnaay.

[ NOTES ]

MANUSCRIPTS

DISCOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Sligter, Jurrien [editor]. Ton de Leeuw, Harwood Academic Publishers GmbH 1995 pp xxiii

- Publishers preface to the score. Forward Music 1988 © Horace Cardew.

- Donemus Muziekgroep Nederland © 1977.

- Prévost, Edwin [editor]. Cornelius Cardew - A Reader. Copula 2006 pp 249.

- NB The tape part was created by the composer. De Leeuw had been professor of composition and electronic music at Sweelinck Conservatory in Amsterdam from 1959-1986.

- Sligter, Jurrien [editor]. Op cit pp 46.

- Sligter, Jurrien [editor]. Op cit pp 73.

- Prévost, Edwin [editor]. Op cit pp 149-227.

- NB Cardew’s original score is headed with a short text by Mao Tse Tung (1934/35): “Mountains! Piercing the blue of heaven, the skies would fall but for your strength supporting”.

- Tilbury, John. Cornelius Cardew A Life Unfinished. Copula 2008 pp 959.

- Sligter, Jurrien [editor]. Op cit pp 75.

- De Groot, Rokus - in Sligter, Jurrien [editor]. Op cit pp 142.

- Sligter, Jurrien [editor]. Op cit pp 93.

MANUSCRIPTS

- Cardew, Cornelius. Mountains, solo bass clarinet. Forward Music 1988 © Horace Cardew

- De Leeuw, Ton. Mountains, bass clarinet & tape. Donemus Muziekgroep Nederland © 1977

DISCOGRAPHY

- Mitchell, Ian / Hobbs, Christopher. The Edge of the World, Black Box 2000

- Sparnaay, Harry / Fusion Moderne. Bass Clarinet Identity, Composers' Voice 1978

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Prévost, Edwin [editor]. Cornelius Cardew - A Reader. Copula 2006

- Sligter, Jurrien [editor]. Ton de Leeuw, Harwood Academic Publishers GmbH 1995

- Tilbury, John. Cornelius Cardew A Life Unfinished. Copula 2008